Digitally Re-Reviewed and Re-Released Tapes

The National Archives is engaged in a digitization for preservation and access project for the Nixon White House Tapes. The National Archives has completed the digitization of the Tapes and is now focused on declassification, re-review and public access. For more information see the "Archival and Processing History" section. Tape audio files and subject log file names that begin with "37-" reflect re-released tapes.

Taping System History

A detailed history of the Nixon White House Tapes from their installation in 1971 to when the National Archives took possession in 1977.

-

On February 16, 1971 the United States Secret Service (USSS), at the request of President Nixon, installed recording devices in the White House. The first devices were installed in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room. Over the course of the next 16 months new locations were added including: the president’s office in the Executive Office Building (EOB), telephones in the Oval Office, EOB office, and the Lincoln Sitting Room. Finally, recording devices were setup at Camp David including the president’s study in Aspen Lodge, and telephones on the president’s desk and study table.

President Nixon was not the first president to record private conversations in the White House. President Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower experimented with recording select meetings and press briefings. However, Kennedy was the first president to extensively record meetings and Johnson continued that practice expanding the scope of recordings. During the 1969 transition Nixon learned that Johnson had recording equipment installed in the White House to record meetings and telephone conversations. According to the president’s Chief of Staff, H. R. Haldeman, Nixon “abhorred” the idea of recording conversations and he had the equipment immediately removed after the inauguration. However, over the next few years Nixon changed his mind about a recording system in response to a number of challenges in fully documenting his presidency with the accuracy he desired.

Nixon was concerned that his meetings were not always reported accurately by participants and he wanted to ensure his private discussions were not misconstrued publicly to the benefit of others during his administration. Haldeman theorized, this may have been due to an individual’s lack of familiarity with the topics discussed but he also believed it was a way for those participants to bolster their own image. Another challenge was documenting presidential meetings with foreign leaders. Nixon preferred meeting with foreign dignitaries using only their interpreter. Nixon thought this lent an air of intimacy to the proceedings, which he believed furthered diplomatic discussions, it also presented a problem of ensuring the translations were accurate. At times, Nixon used a National Security Council (NSC) staff member, who understood the language, but did not attend as a translator. This practice, however, was not consistently followed and it still left gaps in the record. A complete record of his presidency, in order to aid in writing his memoir, was the objective and these methods all fell short.

The Nixon administration tried a number of solutions to keep an accurate record of conversations and meetings. In 1969 and 1970 such efforts included note-takers in meetings or the president taking notes himself, debriefing the president after meetings, and having a note-taker outside the Oval Office catching participants leaving to record their thoughts. Nixon rejected these solutions which he felt were intrusive and did not capture the nuances and details of the conversations. As a last resort, the administration sought to enlist Lt. General Vernon Walters, deputy director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), known for his phenomenal memory, to work for the White House as President Nixon’s personal note-taker. However, General Walters bristled at the idea of being anyone’s note-taker.

Two years into his presidency, Nixon, had still not discovered a solution for documenting meetings. It is unclear who reinitiated discussions about a recording system, however, according to Haldeman, Johnson had a conversation with a friend of Nixon’s regarding the benefits of a taping system while ostensibly discussing the process of setting up a presidential library. Johnson mentioned how helpful the recordings were in preparing his memoirs and how the Nixon Administration was mistaken in dismantling the system. Haldeman discussed the idea of recording his meetings with Nixon who subsequently agreed to set up a recording system in the White House. The challenge was to create a system that was low-maintenance and did not require much of the president––who was not comfortable with technology. Nixon settled on a voice-activated system unlike those of his predecessors. Haldeman believed the president would forget to activate the system when he wanted to record, therefore, the voice activation would ensure that the totality of conversations would be captured. The Secret Service maintained the system and would be responsible for replacing tapes and turning the systems on and off based on the location of the president. Haldeman’s assistants Lawrence M. Higby and Alexander P. Butterfield worked with the Secret Service to install the system.

The recording system went live on February 16, 1971 in the Cabinet Room and the Oval Office. The first set of microphones were placed in the Oval Office––five in the president’s desk and one on each side of the fireplace; and two in the Cabinet Room under the table near the president’s chair. On April 6, the president’s EOB office––four microphones in his desk––and telephones in the Oval Office and the Lincoln Sitting Room were added to the system. Finally, the president’s office and two telephones in Aspen Lodge at Camp David began recording on May 18, 1972. Although Nixon was initially reluctant to record his conversations, once the system was in place he wanted a complete record of conversations which far exceeded anything his predecessors had done. What followed was an almost complete record of the president’s daily conversations until the system was shut down in July 1973.

-

Of utmost importance for the recording system was something that was hands-off for the president who was not tech-savvy. It also needed to be low maintenance for the Secret Service. Alexander Butterfield tasked Alfred Wong, head of Technical Services Division of the Secret Service, to install a system that met these requirements. The taping system was tied into the Secret Service’s presidential locator system. When the president entered a recording area the presidential locator was updated and an agent would set the recorder switch to the record/pause mode. Whenever the voice operated relay microphones detected sound the machines began recording. The machines would continue to record as long as sound was detected and when it became quiet the machines would return to record/pause after 20-30 seconds.

Notably, the Cabinet Room is the only room that was not automatically turned-on with voice activation. While there were on/off switches installed near the president’s place on the Cabinet Room table he in all likelihood never used them. There was another switch installed near Butterfield’s desk and the responsibility for turning this system on and off fell to Butterfield. Often they were left on long after meetings concluded, capturing various sounds including tours, cleaning, and the daily bustle of the White House.

Similarly, when the president entered the Oval Office, the EOB, or his Aspen Lodge study he triggered the activation of the recording machines. Often, when the president was in those rooms, even if he was not speaking, the machines continued, because of ambient noises, television, music, and other noises. These segments are known as room noise and while they are not released to the public archivists review the content to ensure there is no conversation or withdrawn material on them. See processing notes for more information on room noise.

All of the recording stations were equipped with two Sony 800B recorders loaded with extremely thin 0.5mm tape. The recorders had a timer affixed to them that switched which recorder was active every twenty-four hours. During the weekend one recorder remained active for forty-eight hours. In order to keep maintenance low, the recorders operated at the slowest speed, 15/16, which allowed for up to six and a half hours of record time per reel. The quality of tape stock varied and the Sony machines and microphones were not made for recording conversations. All of these conditions have led to the original tapes––and all subsequent copies––to be of generally poor quality which makes listening a challenge.

-

Before Nixon all presidential records were the personal property of the president. After an administration was over the president was allowed to retain legal custody of their records. Presidents would often use their papers to write their memoirs and when finished, traditionally gave their papers back to the American people in the form of a deed of gift. Nixon, therefore, was confident in the precedent that his recordings and papers would remain in his custody like the presidents who proceeded him.

That all changed on Friday July 13, 1973 when in a private interrogation with committee investigators Alexander P. Butterfield revealed the existence of a taping system in the White House. He believed he was just corroborating information that the committee already knew. During his public testimony, three days later on July 16, before the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities––also known as the Ervin Committee after the committees chairman Samuel Ervin––Butterfield revealed to the nation the existence of the White House Tapes. This was the final day the tapes were operational. The Camp David recordings had been completely shut down by late June but after Butterfield’s testimony the remaining recorders were also shut down.

This revelation opened a new avenue in both the Senate investigation and the Special Prosecutor’s investigation. The recordings could help prove the validity of John W. Dean, III’s explosive allegations, before the committee on June 25, 1973, regarding the Nixon Administration or they could bolster the administration’s side of the story. New avenues of investigation also meant new avenues of litigation and obstruction as the Nixon Administration attempted to prevent the release of any tapes. Immediately after Butterfield’s testimony, Nixon directed Secret Service agents not to give testimony regarding their duties. On July 23 the committee voted unanimously to subpoena the tapes which required the president to deliver them to the committee. The Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox requested tapes and after being rebuffed by the administration secured a subpoena.

On July 25 Nixon informed District Court Judge John Sirica he would not comply with Cox’s subpoena citing precedents which showed that presidents could not be “subjected to compulsory process from the courts.” The next day President Nixon wrote to Senator Ervin denying the committee access to the tapes citing executive privilege and separation of powers. Vice Chairman Howard Baker, a Tennessee Republican, suggested suing the President. On August 9 the committee sued the president in federal court. The case was dismissed due to a lack of jurisdiction and that decision was upheld upon appeal. The country now faced a full-blown constitutional crisis.

The Special Prosecutor and the president’s lawyer, Charles Alan Wright, met in court on August 22. Judge Sirica eventually sided with the Special Prosecutor and the administration appealed the decision stating they would only comply with a decision from the highest court in the land. On October 12, the Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Special Prosecutor concluding that the president should turn the tapes over to Judge Sirica. They stated that the president was not above the law but also pleaded with both sides to make an out-of-court settlement. Nixon’s conundrum was to find a way to comply with the order without incriminating himself.

Nixon proposed a compromise to create transcripts of the relevant tapes, give them to the Judge Sirica, and then subsequently fire Cox. Attorney General Elliot Richardson informed the president he would resign if that happened. The president’s new Chief of Staff, Alexander M. Haig, proposed the idea of using John C. Stennis to verify the president’s transcripts. Stennis, although well-respected, was 72 and had long been battling a serious illness. Only recently had he come back to the Senate. It was also well-known that Stennis was hard of hearing. The administration portrayed this as an acceptable method to allow access to the tapes while redacting personal details or national security information before it was submitted to the court. They believed that the only relevant sections of the tapes were those dealing directly with the investigation and wanted to use a broad national security brush to redact segments that were unfavorable to them.

On October 16, the Nixon Administration proposed using a third-party to verify the president’s transcripts. Two days later, Cox rejected the compromise citing he could not rely on a unilateral determination of the evidence. Furthermore, the Nixon Administration only wanted to allow the Special Prosecutor to receive tapes regarding the break-in and cover-up, and Cox wanted tapes that were relevant to other areas of interest in the investigation. On October 20 Nixon ordered Richardson to fire the Special Prosecutor. Richardson resigned, and then the Assistant Attorney General William Ruckelshaus also resigned rather than carry out the order. The third-in-command Solicitor General Robert Bork agreed to carry out the order. This series of events, known as the Saturday Night Massacre, may have delayed the release of the tapes for a time, but the event ensured they would eventually be released.

The firing of Cox on October 20 led to a firestorm of disapproval in Congress and around the country. In November Leon Jaworski accepted the position of Special Prosecutor and with the backing of a more confrontational Senate, he had more independence and protection than his predecessor. Soon afterwards the Special Prosecutor was informed that two tapes requested were missing and that the tape for June 20, 1972 had an 18 ½ minute gap. The Nixon Administration stated the erasure was accidental, and the president’s personal secretary, Rose Mary Woods, claimed she had inadvertently erased that portion of tape. On November 26 lawyers for the president released seven tapes to Judge Sirica and after listening to the tapes Sirica released a portion of them to Jaworski on December 21. Those tape segments proved helpful in corroborating the case against the administration. The grand jury indicted a number of the president’s aides, and in May, Haig was informed by Jaworski, that the president had been named as an unindicted co-conspirator.

On April 16, 1974 Jaworski issued a subpoena asking for sixty-four additional tapes. The president once again opposed the subpoena in court, citing executive privilege and separation of powers. Judge Sirica ruled against the president on May 20 which gave the administration until the May 31 to comply or appeal. The president appealed and Jaworski asked the Supreme Court to take immediate jurisdiction. On July 8 the Special Prosecutor and the president’s lawyer, James St. Clair, presented their arguments before the Supreme Court. United States v. Nixon was an unanimous 8-0 decision; Associate Justice William Rehnquist recused himself, against the president. Handed down on July 24 the decision effectively ended the presidency of Richard Nixon and allowed the Special Prosecutor access to all the tapes that were subpoenaed––including the June 23, 1972 tape which contained the “smoking gun” conversation.

-

Richard Nixon resigned on August 9 and within one month the former president signed an agreement with the Administrator for the General Services, Arthur F. Sampson. This contract, the Nixon-Sampson Agreement, covered all the tapes and documents of the Nixon presidency. It stipulated that the government would keep all materials in a federal facility behind a two-key system. Access would require the approval of both Nixon and the administrator (or their proxies). Nixon could access the materials for judicial cases and the tapes would become government property on September 1, 1979. However, Nixon reserved the right to order their destruction at any time. Furthermore, the agreement required the tapes to be destroyed on September 1, 1984 or upon Nixon’s death, whichever happened first. Lawsuits sprang up immediately seeking to void this agreement. Congress stepped in and passed the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act (PRMPA). On December 19, 1974, President Gerald R. Ford signed PRMPA.

PRMPA stated that the Archivist of the United States shall retain complete possession and control of original recordings, as well as all papers, documents, other materials created during the Nixon administration that had historical or commemorative value. The act allowed for access to the materials by former President Nixon and the Watergate Special Prosecution Force, as well as for the purpose of legal discovery and ongoing governmental business. Section 104 of PRMPA mandated that the General Services Administration (GSA), of which NARA was originally part of as the National Archives Records Service (NARS), submit to each house of Congress a set of proposed regulations describing procedures for processing and providing public access to the Nixon Presidential materials in its possession. Section 105 of PRMPA provided the Federal Court for the District of Columbia (DDC) with exclusive jurisdiction to hear cases challenging the legal or constitutional validity of the act or implementing regulations. DDC also retained jurisdiction to settle disputes involving custody and control over the materials or compensation resulting from the seizure of the materials.

The US Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of PRMPA in Nixon v. Administrator of General Services. The Supreme Court's decision on June 28, 1977, allowed the National Archives to take possession of the Nixon Presidential materials. In a memorandum signed on July 29, 1977, by Counsel to the President Robert J. Lipshutz and GSA Administrator Jay Solomon, the White House Office of Counsel formally transferred custody and control over the Nixon Presidential materials to the National Archives. On August 9, 1977, sensitive Presidential materials, including Haldeman's Diary, were transferred from the EOB to a vault within the National Archives.

Soon after the Supreme Court handed down its decision, GSA submitted a set of implementing regulations to Congress which was approved on December 26, 1977, and became effective on January 16, 1978. The fourth set of implementing regulations refined the meaning of presidential historical materials to include materials made or received by the president and his staff in fulfilling their constitutional and statutory duties of the Office of the President. The regulations further distinguished presidential materials from private or personal materials which relate only to an individual's family or non-public affairs. The implementing regulations also stipulated that the National Archives must prioritize the identification and segregation of personal materials interfiled with presidential materials, and return any personal materials to their owner in a timely manner. With formalized definitions of presidential and personal materials in place, a distinction could now be made under PRMPA between materials for retention by archivists and others that must be returned to individuals.

Finding Aids

-

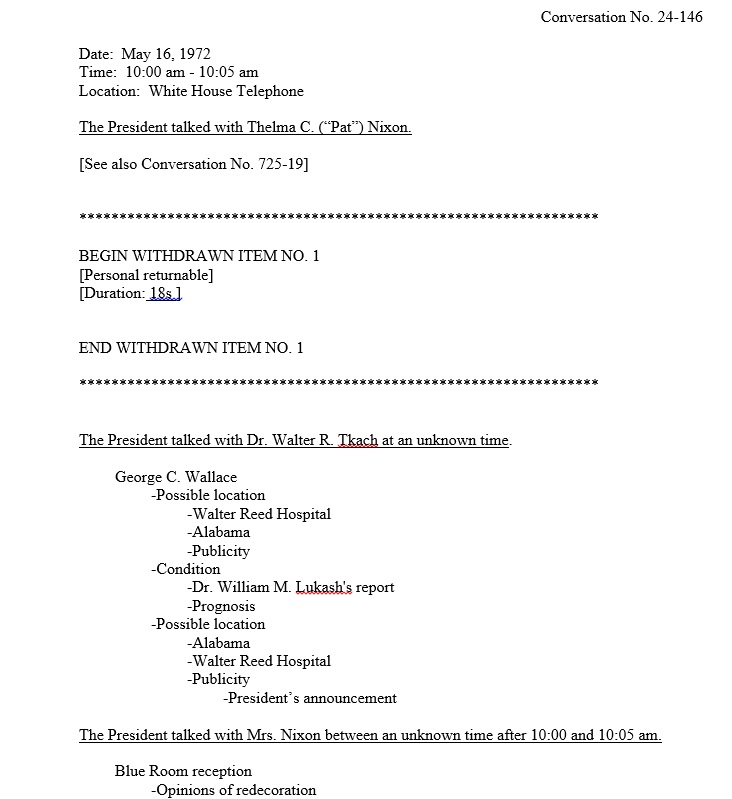

Each tape has a Tape Subject Log as the archival finding aid. A log indicates each conversation, the date, time, location, participants, and includes action statement in particular highlighting participants movements. Each conversation on a tape then has an hierarchical outline of topics discussed in the conversation. Any withdrawal within a conversation will be identified at the point where it occurs. For more information please see the Archival Processing section.

All Tape Subject Logs are available in our PDF Index.

Below is a sample of a logged conversation.

-

Transcripts and audio related to White House Tapes played in court as part of Watergate trials.

Watergate Special Prosecution Force

Transcripts created by the Special Prosecutor during the course of the investigation.

Prisoner of War/Missing in Action Transcripts

Transcripts created as part of a special project.

Automobile Safety and Airbag Transcript

Transcripts created as part of a court case.

Transcripts and audio of select conversations segments related to Nixon's trip to China.

-

- To download the CD-ROM contents as a .zip file (including a Searchable Index, Logs and/or Transcripts, and Scope and Content Notes), click here. To download, right click on link and select "Save Link" or "Save Target" to your computer. Extracting the files requires file extraction software, such as StuffIt or WinZip, that can "unzip" (open) the compressed .zip file, once it is completely downloaded on your computer. Please note: the file is 230 MB.

-

A Portable Document Format (PDF) version of the complete archival finding aid for the White House Tapes. Much of the information in this finding aid make up the contents of this page.

Online Listening

Generally conversations from July 1972 - July 1973, excluding Cabinet Room conversations are online. Those tapes include:

- White House Telephone: Audiotapes 027-041; 043-046

- Camp David Study Table Phone: Audiotapes 137-169

- Camp David Study Desk Phone: Audiotapes 176-186

- Camp David Hard Wire: Audiotapes 196-244

- Executive Office Building: Audiotapes 348-448

- Oval Office: Audiotapes 746-950

Tapes will be added as the National Archives continues its digitization project. For Tapes still pending online release, contact the Nixon Library to explore copies.

-

Audiotape 001 Audiotape 002 Audiotape 003 Audiotape 004 Audiotape 005 Audiotape 006

Audiotape 007 Audiotape 008 Audiotape 009 Audiotape 010 Audiotape 011 Audiotape 012

Audiotape 013 Audiotape 014 Audiotape 015 Audiotape 016 Audiotape 017 Audiotape 018

Audiotape 019 Audiotape 020 Audiotape 021 Audiotape 022 Audiotape 023 Audiotape 024

Audiotape 025 Audiotape 026 Audiotape 027 Audiotape 028 Audiotape 029 Audiotape 030

Audiotape 031 Audiotape 032 Audiotape 033 Audiotape 034 Audiotape 035 Audiotape 036

Audiotape 037 Audiotape 038 Audiotape 039 Audiotape 040 Audiotape 041 Audiotape 042

-

Audiotape 047 Audiotape 048 Audiotape 049 Audiotape 050 Audiotape 051 Audiotape 052

Audiotape 053 Audiotape 054 Audiotape 055 Audiotape 056 Audiotape 057 Audiotape 058

Audiotape 059 Audiotape 060 Audiotape 061 Audiotape 062 Audiotape 063 Audiotape 064

Audiotape 065 Audiotape 066 Audiotape 067 Audiotape 068 Audiotape 069 Audiotape 070

Audiotape 071 Audiotape 072 Audiotape 073 Audiotape 074 Audiotape 075 Audiotape 076

Audiotape 077 Audiotape 078 Audiotape 079 Audiotape 080 Audiotape 081 Audiotape 082

Audiotape 083 Audiotape 084 Audiotape 085 Audiotape 086 Audiotape 087 Audiotape 088

Audiotape 089 Audiotape 090 Audiotape 091 Audiotape 092 Audiotape 093 Audiotape 094

Audiotape 095 Audiotape 096 Audiotape 097 Audiotape 098 Audiotape 099 Audiotape 100

Audiotape 101 Audiotape 102 Audiotape 103 Audiotape 104 Audiotape 105 Audiotape 106

Audiotape 107 Audiotape 108 Audiotape 109 Audiotape 110 Audiotape 111 Audiotape 112

Audiotape 113 Audiotape 114 Audiotape 115 Audiotape 116 Audiotape 117 Audiotape 118

Audiotape 119 Audiotape 120 Audiotape 121 Audiotape 122 Audiotape 123 Audiotape 124

Audiotape 125 Audiotape 126 Audiotape 127 Audiotape 128 Audiotape 129

-

Audiotape 130 Audiotape 131 Audiotape 132 Audiotape 133 Audiotape 134 Audiotape 135

Audiotape 136 Audiotape 137 Audiotape 138 Audiotape 139 Audiotape 140 Audiotape 141

Audiotape 142 Audiotape 143 Audiotape 144 Audiotape 145 Audiotape 146 Audiotape 147

Audiotape 148 Audiotape 149 Audiotape 150 Audiotape 151 Audiotape 152 Audiotape 153

Audiotape 154 Audiotape 155 Audiotape 156 Audiotape 157 Audiotape 158 Audiotape 159

Audiotape 160 Audiotape 161 Audiotape 162 Audiotape 163 Audiotape 164 Audiotape 165

-

Audiotape 170 Audiotape 171* Audiotape 172 Audiotape 173* Audiotape 174 Audiotape 175*

Audiotape 176 Audiotape 177 Audiotape 178 Audiotape 179 Audiotape 180 Audiotape 181

Audiotape 182 Audiotape 183 Audiotape 184 Audiotape 185 Audiotape 186 Audiotape 187*

* Denotes a blank tape see Archival and Processing History - The First Review: 1978-1993 for more information regarding these tapes.

-

Audiotape 188 Audiotape 189 Audiotape 190 Audiotape 191 Audiotape 192 Audiotape 193

Audiotape 194 Audiotape 195 Audiotape 196 Audiotape 197 Audiotape 198 Audiotape 199

Audiotape 200 Audiotape 201 Audiotape 202 Audiotape 203 Audiotape 204 Audiotape 205

Audiotape 206 Audiotape 207 Audiotape 208 Audiotape 209 Audiotape 210 Audiotape 211

Audiotape 212 Audiotape 213 Audiotape 214 Audiotape 215 Audiotape 216 Audiotape 217

Audiotape 218 Audiotape 219 Audiotape 220 Audiotape 221 Audiotape 222 Audiotape 223

Audiotape 224 Audiotape 225 Audiotape 226 Audiotape 227 Audiotape 228 Audiotape 229

Audiotape 230 Audiotape 231 Audiotape 232 Audiotape 233 Audiotape 234 Audiotape 235

Audiotape 236 Audiotape 237 Audiotape 238 Audiotape 239 Audiotape 240 Audiotape 241

-

Audiotape 245 Audiotape 246 Audiotape 247 Audiotape 248 Audiotape 249 Audiotape 250

Audiotape 251 Audiotape 252 Audiotape 253 Audiotape 254 Audiotape 255 Audiotape 256

Audiotape 257 Audiotape 258 Audiotape 259 Audiotape 260 Audiotape 261 Audiotape 262

Audiotape 263 Audiotape 264 Audiotape 265 Audiotape 266 Audiotape 267 Audiotape 268

Audiotape 269 Audiotape 270 Audiotape 271 Audiotape 272 Audiotape 273 Audiotape 274

Audiotape 275 Audiotape 276 Audiotape 277 Audiotape 278 Audiotape 279 Audiotape 280

Audiotape 281 Audiotape 282 Audiotape 283 Audiotape 284 Audiotape 285 Audiotape 286

Audiotape 287 Audiotape 288 Audiotape 289 Audiotape 290 Audiotape 291 Audiotape 292

Audiotape 293 Audiotape 294 Audiotape 295 Audiotape 296 Audiotape 297 Audiotape 298

Audiotape 299 Audiotape 300 Audiotape 301 Audiotape 302 Audiotape 303 Audiotape 304

Audiotape 305 Audiotape 306 Audiotape 307 Audiotape 308 Audiotape 309 Audiotape 310

Audiotape 311 Audiotape 312 Audiotape 313 Audiotape 314 Audiotape 315 Audiotape 316

Audiotape 317 Audiotape 318 Audiotape 319 Audiotape 320 Audiotape 321 Audiotape 322

Audiotape 323 Audiotape 324 Audiotape 325 Audiotape 326 Audiotape 327 Audiotape 328

Audiotape 329 Audiotape 330 Audiotape 331 Audiotape 332 Audiotape 333 Audiotape 334

Audiotape 335 Audiotape 336 Audiotape 337 Audiotape 338 Audiotape 339 Audiotape 340

Audiotape 341 Audiotape 342 Audiotape 343 Audiotape 344 Audiotape 345 Audiotape 346

Audiotape 347 Audiotape 348 Audiotape 349 Audiotape 350 Audiotape 351 Audiotape 352

Audiotape 353 Audiotape 354 Audiotape 355 Audiotape 356 Audiotape 357 Audiotape 358

Audiotape 359 Audiotape 360 Audiotape 361 Audiotape 362 Audiotape 363 Audiotape 364

Audiotape 365 Audiotape 366 Audiotape 367 Audiotape 368 Audiotape 369 Audiotape 370

Audiotape 371 Audiotape 372 Audiotape 373 Audiotape 374 Audiotape 375 Audiotape 376

Audiotape 377 Audiotape 378 Audiotape 379 Audiotape 380 Audiotape 381 Audiotape 382

Audiotape 383 Audiotape 384 Audiotape 385 Audiotape 386 Audiotape 387 Audiotape 388

Audiotape 389 Audiotape 390 Audiotape 391 Audiotape 392 Audiotape 393 Audiotape 394

Audiotape 395 Audiotape 396 Audiotape 397 Audiotape 398 Audiotape 399 Audiotape 400

Audiotape 401 Audiotape 402 Audiotape 403 Audiotape 404 Audiotape 405 Audiotape 406

Audiotape 407 Audiotape 408 Audiotape 409 Audiotape 410 Audiotape 411 Audiotape 412

Audiotape 413 Audiotape 414 Audiotape 415 Audiotape 416 Audiotape 417 Audiotape 418

Audiotape 419 Audiotape 420 Audiotape 421 Audiotape 422 Audiotape 423 Audiotape 424

Audiotape 425 Audiotape 426 Audiotape 427 Audiotape 428 Audiotape 429 Audiotape 430

Audiotape 431 Audiotape 432 Audiotape 433 Audiotape 434 Audiotape 435 Audiotape 436

Audiotape 437 Audiotape 438 Audiotape 439 Audiotape 440 Audiotape 441 Audiotape 442

Audiotape 443 Audiotape 444 Audiotape 445 Audiotape 446 Audiotape 447 Audiotape 448

-

Audiotape 449 Audiotape 450 Audiotape 451 Audiotape 452 Audiotape 453 Audiotape 454

Audiotape 455 Audiotape 456 Audiotape 457 Audiotape 458 Audiotape 459 Audiotape 460

Audiotape 461 Audiotape 462 Audiotape 463 Audiotape 464 Audiotape 465 Audiotape 466

Audiotape 467 Audiotape 468 Audiotape 469 Audiotape 470 Audiotape 471 Audiotape 472

Audiotape 473 Audiotape 474 Audiotape 475 Audiotape 476 Audiotape 477 Audiotape 478

Audiotape 479 Audiotape 480 Audiotape 481 Audiotape 482 Audiotape 483 Audiotape 484

Audiotape 485 Audiotape 486 Audiotape 487 Audiotape 488 Audiotape 489 Audiotape 490

Audiotape 491 Audiotape 492 Audiotape 493 Audiotape 494 Audiotape 495 Audiotape 496

Audiotape 497 Audiotape 498 Audiotape 499 Audiotape 500 Audiotape 501 Audiotape 502

Audiotape 503 Audiotape 504 Audiotape 505 Audiotape 506 Audiotape 507 Audiotape 508

Audiotape 509 Audiotape 510 Audiotape 511 Audiotape 512 Audiotape 513 Audiotape 514

Audiotape 515 Audiotape 516 Audiotape 517 Audiotape 518 Audiotape 519 Audiotape 520

Audiotape 521 Audiotape 522 Audiotape 523 Audiotape 524 Audiotape 525 Audiotape 526

Audiotape 527 Audiotape 528 Audiotape 529 Audiotape 530 Audiotape 531 Audiotape 532

Audiotape 533 Audiotape 534 Audiotape 535 Audiotape 536 Audiotape 537 Audiotape 538

Audiotape 539 Audiotape 540 Audiotape 541 Audiotape 542 Audiotape 543 Audiotape 544

Audiotape 545 Audiotape 546 Audiotape 547 Audiotape 548 Audiotape 549 Audiotape 550

Audiotape 551 Audiotape 552 Audiotape 553 Audiotape 554 Audiotape 555 Audiotape 556

Audiotape 557 Audiotape 558 Audiotape 559 Audiotape 560 Audiotape 561 Audiotape 562

Audiotape 563 Audiotape 564 Audiotape 565 Audiotape 566 Audiotape 567 Audiotape 568

Audiotape 569 Audiotape 570 Audiotape 571 Audiotape 572 Audiotape 573 Audiotape 574

Audiotape 575 Audiotape 576 Audiotape 577 Audiotape 578 Audiotape 579 Audiotape 580

Audiotape 581 Audiotape 582 Audiotape 583 Audiotape 584 Audiotape 585 Audiotape 586

Audiotape 587 Audiotape 588 Audiotape 589 Audiotape 590 Audiotape 591 Audiotape 592

Audiotape 593 Audiotape 594 Audiotape 595 Audiotape 596 Audiotape 597 Audiotape 598

Audiotape 599 Audiotape 600* Audiotape 601 Audiotape 602 Audiotape 603 Audiotape 604

Audiotape 605 Audiotape 606 Audiotape 607 Audiotape 608 Audiotape 609 Audiotape 610

Audiotape 611 Audiotape 612 Audiotape 613 Audiotape 614 Audiotape 615 Audiotape 616

Audiotape 617 Audiotape 618 Audiotape 619 Audiotape 620 Audiotape 621 Audiotape 622

Audiotape 623 Audiotape 624 Audiotape 625 Audiotape 626 Audiotape 627 Audiotape 628

Audiotape 629 Audiotape 630 Audiotape 631 Audiotape 632 Audiotape 633 Audiotape 634

Audiotape 635 Audiotape 636 Audiotape 637 Audiotape 638 Audiotape 639 Audiotape 640

Audiotape 641 Audiotape 642 Audiotape 643 Audiotape 644 Audiotape 645 Audiotape 646

Audiotape 647 Audiotape 648 Audiotape 649 Audiotape 650 Audiotape 651 Audiotape 652

Audiotape 653 Audiotape 654 Audiotape 655 Audiotape 656 Audiotape 657 Audiotape 658

Audiotape 659 Audiotape 660 Audiotape 661 Audiotape 662 Audiotape 663 Audiotape 664

Audiotape 665 Audiotape 666 Audiotape 667 Audiotape 668 Audiotape 669 Audiotape 670

Audiotape 671 Audiotape 672 Audiotape 673 Audiotape 674 Audiotape 675 Audiotape 676

Audiotape 677 Audiotape 678 Audiotape 679 Audiotape 680* Audiotape 681 Audiotape 682

Audiotape 683 Audiotape 684 Audiotape 685 Audiotape 686 Audiotape 687 Audiotape 688

Audiotape 689 Audiotape 690 Audiotape 691 Audiotape 692 Audiotape 693 Audiotape 694

Audiotape 695 Audiotape 696 Audiotape 697 Audiotape 698 Audiotape 699 Audiotape 700

Audiotape 701 Audiotape 702 Audiotape 703 Audiotape 704 Audiotape 705 Audiotape 706

Audiotape 707 Audiotape 708 Audiotape 709 Audiotape 710 Audiotape 711 Audiotape 712

Audiotape 713 Audiotape 714 Audiotape 715 Audiotape 716 Audiotape 717 Audiotape 718

Audiotape 719 Audiotape 720 Audiotape 721 Audiotape 722 Audiotape 723 Audiotape 724

Audiotape 725 Audiotape 726 Audiotape 727 Audiotape 728 Audiotape 729 Audiotape 730

Audiotape 731 Audiotape 732 Audiotape 733 Audiotape 734 Audiotape 735 Audiotape 736

Audiotape 737 Audiotape 738 Audiotape 739 Audiotape 740 Audiotape 741 Audiotape 742

Audiotape 743 Audiotape 744 Audiotape 745 Audiotape 746 Audiotape 747 Audiotape 748

Audiotape 749 Audiotape 750 Audiotape 751 Audiotape 752 Audiotape 753 Audiotape 754

Audiotape 755 Audiotape 756 Audiotape 757 Audiotape 758 Audiotape 759 Audiotape 760

Audiotape 761 Audiotape 762 Audiotape 763 Audiotape 764 Audiotape 765 Audiotape 766

Audiotape 767 Audiotape 768 Audiotape 769 Audiotape 770 Audiotape 771 Audiotape 772

Audiotape 773 Audiotape 774 Audiotape 775 Audiotape 776 Audiotape 777 Audiotape 778

Audiotape 779 Audiotape 780 Audiotape 781 Audiotape 782 Audiotape 783 Audiotape 784

Audiotape 785 Audiotape 786 Audiotape 787 Audiotape 788 Audiotape 789 Audiotape 790

Audiotape 791 Audiotape 792 Audiotape 793 Audiotape 794 Audiotape 795 Audiotape 796

Audiotape 797 Audiotape 798 Audiotape 799 Audiotape 800 Audiotape 801 Audiotape 802

Audiotape 803 Audiotape 804 Audiotape 805 Audiotape 806 Audiotape 807 Audiotape 808

Audiotape 809 Audiotape 810 Audiotape 811 Audiotape 812 Audiotape 813 Audiotape 814

Audiotape 815 Audiotape 816 Audiotape 817 Audiotape 818 Audiotape 819 Audiotape 820

Audiotape 821 Audiotape 822 Audiotape 823 Audiotape 824 Audiotape 825 Audiotape 826

Audiotape 827 Audiotape 828 Audiotape 829 Audiotape 830 Audiotape 831 Audiotape 832

Audiotape 833 Audiotape 834 Audiotape 835 Audiotape 836 Audiotape 837 Audiotape 838

Audiotape 839 Audiotape 840 Audiotape 841 Audiotape 842 Audiotape 843 Audiotape 844

Audiotape 845 Audiotape 846 Audiotape 847 Audiotape 848 Audiotape 849 Audiotape 850

Audiotape 851 Audiotape 852 Audiotape 853 Audiotape 854 Audiotape 855 Audiotape 856

Audiotape 857 Audiotape 858 Audiotape 859 Audiotape 860 Audiotape 861 Audiotape 862

Audiotape 863 Audiotape 864 Audiotape 865 Audiotape 866 Audiotape 867 Audiotape 868

Audiotape 869 Audiotape 870 Audiotape 871 Audiotape 872 Audiotape 873 Audiotape 874

Audiotape 875 Audiotape 876 Audiotape 877 Audiotape 878 Audiotape 879 Audiotape 880

Audiotape 881 Audiotape 882 Audiotape 883 Audiotape 884 Audiotape 885 Audiotape 886

Audiotape 887 Audiotape 888 Audiotape 889 Audiotape 890 Audiotape 891 Audiotape 892

Audiotape 893 Audiotape 894 Audiotape 895 Audiotape 896 Audiotape 897 Audiotape 898

Audiotape 899 Audiotape 900 Audiotape 901 Audiotape 902 Audiotape 903 Audiotape 904

Audiotape 905 Audiotape 906 Audiotape 907 Audiotape 908 Audiotape 909 Audiotape 910

Audiotape 911 Audiotape 912 Audiotape 913 Audiotape 914 Audiotape 915 Audiotape 916

Audiotape 917 Audiotape 918 Audiotape 919 Audiotape 920 Audiotape 921 Audiotape 922

Audiotape 923 Audiotape 924 Audiotape 925 Audiotape 926 Audiotape 927 Audiotape 928

Audiotape 929 Audiotape 930 Audiotape 931 Audiotape 932 Audiotape 933 Audiotape 934

Audiotape 935 Audiotape 936 Audiotape 937 Audiotape 938 Audiotape 939 Audiotape 940

Audiotape 941 Audiotape 942 Audiotape 943 Audiotape 944 Audiotape 945 Audiotape 946

Audiotape 947 Audiotape 948 Audiotape 949 Audiotape 950*

* Denotes a blank tape see Archival and Processing History - The First Review: 1978-1993 for more information regarding these tapes.

-

- Conversation Number: 001-021

Date: April 7, 1971

Abstract: Telephone conversation between the President and Henry Kissinger, the President asks if Kissinger has heard any reaction to his just delivered Vietnam speech and complaints about the military.

- Conversation Number: 475-023

Date: April 8, 1971

Abstract: The President and US Ambassador to Iran Douglas MacArthur II talking frankly about problems in the Middle East and US policy towards Israel.

- Conversation Number: 002-002

Date: April 19, 1971

Abstract: The President orders Deputy Attorney General Richard Kleindienst to drop a Department of Justice appeal of a corporate merger involving the ITT corporation.

- Conversation Number: 534-002(3)

Date: July 1, 1971

Abstract: The President instructs his Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman to have someone break into the Brookings Institution and "clean out" the secret documents in their safes. Kissinger is present during this conversation.

- Conversation Number: 541-002

Date: July 21, 1971

Abstract: The President, H.R. Haldeman, and John Connolly discuss replacing Spiro Agnew as Vice President. Nixon offers the position to Connolly who turns him down.

- Conversation Number: 542-006

Date: July 22, 1971

Abstract: Oval Office conversation between the President and White House Counsellor Donald Rumsfeld discussing Vice President Agnew's problems in dealing with the press.

- Conversation Number: 587-007

Date: October 8, 1971

Abstract: Oval Office conversation in which the President and his chief domestic policy advisor John Ehrlichman are preparing for a meeting with CIA Director Richard Helms. Ehrlichman wants access to CIA documents about the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Ngo Dinh Diem coup in South Vietnam in 1963, and other previous administrations intelligence operations. Ehrlichman informs the President how he plans to use this information once received. Some of this information was later used in composing a forged cable showing President Kennedy's involvement in the assassination of Diem.

- Conversation Number: 590-002

Date: October 13, 1971

Abstract: Oval Office conversation between the President and Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman discussing the press contingent for the President's forthcoming visit to the People's Republic of China.

- Conversation Number: 011-105

Date: October 17, 1971

Abstract: A telephone conversation between the President and Secretary of State William Rogers regarding US strategy on the upcoming United Nations General Assembly vote on whether to expel Taiwan from the UN.

- Conversation Number: 011-143

Date: October 19, 1971

Abstract: The President and Attorney General John Mitchell discuss appointing William Rehnquist to the Supreme Court.

- Conversation Number: 013-008

Date: October 26, 1971

Abstract: A telephone conversation between the President and California Governor Ronald Reagan after the UN votes to expel Taiwan from the UN General Assembly.

- Conversation Number: 294-006

Date: November 18, 1971

Abstract: Old Executive Office Building office conversation in which the President and Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman discuss the annual "photo op" for Thanksgiving.

- Conversation Number: 624-021

Date: November 24, 1971

Abstract: The President, Henry Kissinger and Secretary of State William Rogers change the US government policy of neutrality in the India-Pakistan War and secretly "tilt" toward Pakistan.

- Conversation Number: 017-021

Date: December 31, 1971

Abstract: Telephone call to UN Ambassador George Bush on New Years Eve. Nixon is still in the Oval Office working. He calls to thank Bush for his work during the Taiwan debate and efforts to stave off an India-Pakistan conflict.

- Conversation Number: 022-006

Date: March 23, 1972

Abstract: Telephone conversation between the President and Press Secretary Ronald Ziegler in which the President complains about former US ambassador to Chile Edward Korry's testimony in Congress regarding the 1970 Chilean election.

- Conversation Number: 701-009

Date: April 4, 1972

Abstract: Oval Office conversation between the President and H.R. Haldeman discussing the press and public relations.

- Conversation Number: 191-018 (segment 1)

Date: May 18, 1972

Abstract: Conversation from the Presidential retreat at Camp David. The President and Henry Kissinger are discussing Kissinger's previous meeting with Ivy League college presidents who met with him in the aftermath of the President's decision to mine Haiphong harbor and escalate bombing in North Vietnam on May 8, 1972.

- Conversation Number: 191-018 (segment 2)

Date: May 18, 1972

Abstract: A second excerpt from the May 18, 1972 Camp David conversation between the President and Henry Kissinger.

- Conversation Number: 726-001

Date: May 19, 1972

Abstract: Oval Office meeting between President Nixon, Vice President Spiro Agnew, Henry Kissinger, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Thomas Moorer. Nixon is insistent that the Air Force conduct bombing sorties in accordance with his instructions and orders.

- Conversation Number: 035-035

Date: December 28, 1972

Time: 4:00 pm - 4:15 pm

Location: White House Telephone

Abstract: In this excerpt, President Nixon discussed with his National Security Advisor Henry A. Kissinger the effectiveness of the bombing of the Hanoi and Haiphong areas in North Vietnam that had begun on December 18. They discussed the North Vietnamese decision to return to negotiations for a peace agreement and their options for convincing the South Vietnamese to accept a settlement.

- Conversation Number: 153-020

Date: November 14, 1972

Time: 2:40 pm - 3:08 pm

Location: Camp David Study Table

Abstract: In this excerpt, President Nixon talked with his aide Charles W. Colson about his landslide victory over George S. McGovern in the 1972 presidential election and the reasons for his reelection.

- Conversation Number: 157-026

Date: December 9, 1972

Time: 12:22 pm - 12:58 pm

Location: Camp David Study Table

Abstract: In this excerpt, President Nixon discussed with his aide Charles W. Colson his efforts to build a "New Majority" coalition of conservatives including traditionally working class members of the Democratic Party. They talked about the appointment of building trades union leader Peter J. Brennan as Secretary of Labor and the opportunities this would bring for reaching out to workers.

- Conversation Number: 035-078

Date: January 3, 1973

Time: 8:39 pm - 8:59 pm

Location: White House Telephone

Abstract: In this excerpt, President Nixon talked with his aide Charles W. Colson about the administration's relations with the Washington Post as the Watergate investigation proceeded.

- Conversation Number: 035-051

Date: January 2, 1973

Time: 8:56 am - 9:03 am

Location: White House Telephone

Abstract: In this excerpt, President Nixon discussed with Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger pending Supreme Court cases including the landmark pornography case Miller v. California and the President's appointments to the Court including William H. Rehnquist.

- Conversation Number: 001-021

Date: April 7, 1971

Archival and Processing History

A processing history of the Nixon White House Tapes from 1978 through the present.

-

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) took physical possession of the White House Tapes in August of 1977. From March through April of 1978, NARA’s primary focus was on creating a preservation copy of the original tapes. The original tapes were .5 mil and 6 ½ hours long and they were recorded at the very slow speed 15/16 inches per second (ips). NARA staff rewound the original tapes onto larger seven inch reel with a four inch hub which provided a tighter, more even wind. The preservation duplicate was on 1.0 mil tape and it was recorded at 3 ¾ ips. This copy is known as the “S-Copy”. However, because of ongoing legal disputes, at this time, NARA was not permitted to listen to the tapes and instead had to complete the duplication process by monitoring signal levels on the machines.

By September 1978, NARA had finished the duplication and started to processes the tapes in order to gain intellectual control over the collection. The original tape boxes had very little information about the content of the tapes and usually only included an approximate date of creation. Archivists listened to the tapes to start piecing together participants, subjects, date, location etcetera. This process also included a review of the content to identify restricted sections of each conversation in accordance with PRMPA, and its implementing public access regulations––which is more fully described below. During this period the existence of seven blank reels of tape was discovered: 171, 173, 175, 187, 600, 680, and 950. These reels may have been placed on the recorders but were never used. Nonetheless they were given number designations. They are currently arranged as the Blank Sound Recording Series.

Despite gaining more intellectual control over the collection archivists needed a solution for quickly and consistently navigating the tapes to find specific conversations and restrictions in order to comply with PRMPA and the various legal decisions. To solve this problem, NARA created another duplication of the tapes for reference use. This copy, known as the “Enhanced Masters,” had additional technical processing which included spectrum analysis, signal boosting, noise removal, and each tape was stamped with Society of Motion Picture & Television Engineers (SMPTE) timecode. The Enhanced Masters were made on 3 ¾ ips and 1.5 millimeter tape. Each reel was approximately one-hour long with multiple reels making up a full tape. The timecode enabled archivists to fully comply with PRMPA restrictions.

Now that archivists could accurately pinpoint segments of the tapes they began a comprehensive review of the tapes. Under PRMPA, and a subsequent agreement in 1979, NARA was required to return personal and private conversations to the former president. Any conversation where Nixon was not using the constitutional or statutory powers of the office of the Presidency was considered personal. Therefore, conversations with his family and conversations where he was acting as the head of the Republican Party––and speaking purely in his private political role––were to be returned.

All presidential conversations had to be reviewed by NARA under PRMPA guidelines and segments found to have restricted content were separated into their proper PRMPA categories. The PRMPA guidelines define eight restriction categories:

A: Violate a Federal statute or agency policy;

B: Reveal national security information;

C: Violate an individual’s rights (pending);

D: Constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy;

E: Disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or financial information;

F: Disclose investigatory/law enforcement information;

G: Disclose purely private and personal information, as defined by the PRMPA;

H: Disclose non-historical material.

During this review, NARA was also required by court subpoenas to provide transcriptions for sections of conversations needed in court. (Previously, some transcripts were created by the FBI and the Special Prosecutor during the Watergate investigations.) This process was incredibly time consuming and it was impossible to guarantee 100 percent accuracy, therefore, NARA created detailed subject logs of all conversations except when mandated by the courts to create a transcript. The subject logs described the main conversation topics, sub-topics, participants, entrances and exits by staff, and telephone calls. Paired with the Presidential Daily Diary, archivists were able to add exact time of day or approximate time of day to each room and telephone conversation.

The review process was detailed and comprehensive. Each tape had a processing folder which held all documentation regarding that tape. The tape was then reviewed by two archivists, both of which listened to it in its entirety. During the first review, an archivist created a detailed subject log of the topics and people in the conversation, marked the movement of staff in and out of the office space, and flagged PRMPA restriction categories. To aide in review archivists used a plethora of historical sources––including the Presidential Daily Diary, Public Papers, staff memorandum, and any other pertinent primary and secondary sources––in order to ensure historical context for the conversations. Withdrawal sheets were also created in order to document decisions regarding the PRMPA restrictions. These sheets listed the beginning and ending timecode, the beginning and ending keywords, and the restriction category of the withdrawal. After the completion of this review a second, more senior, archivist re-reviewed the tape to verify the first reviewer’s decisions. After a thorough review the tape was passed on to Archives Specialists for editing.

Upon receiving the reviewed tape, Archives Specialists used the reviewer’s decisions to physically delete the restricted content from the tape and splice in 10 seconds of blank leader tape. These blank leaders were marked with the tape, conversation, and withdrawal number. Similarly, blank leader tape was spliced onto the restricted tape sections with the identifying information and all of these were spliced together into a large reel based on PRMPA restriction category. This method allowed for any withdrawal to be easily found and reinserted back into a conversation when appropriate. All of these changes were made to the “Enhanced Masters” and the “S-Copy” remained untouched.

In the late 1980’s a dispute arose between the Nixon and NARA. After releasing twelve-hours of conversations and transcripts created by the Watergate Special Prosecution Force (WSPF), which were played in court during the Watergate trials, NARA prepared to release the rest of the subpoenaed tapes, however, the former president sought to block their release. The release of these tapes was delayed until 1991. This delay was also coupled with a decision by the NARA to re-review all the tapes. This controversial decision led to a large turnover in staff who disagreed with NARA’s decision to re-review the tapes.

On May 17, 1993 three-hours of Abuse of Governmental Power (AOGP) conversations were released by the NARA. One of the primary directives of PRMPA was “to provide the public with the full truth, at the earliest reasonable date, of the abuses of governmental powers popularly identified under the generic term “Watergate”.” While many of these conversations were identified by the WSPF, many were not, and archivists identified conversations that met this standard based on the criteria which were investigated by the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities 1972. The ten categories were:

- Misuse of Government Agencies

- Watergate break-in

- Watergate cover-up

- Campaign practices

- Obstruction of Justice

- Campaign financing

- Milk Fund Investigation

- Hughes-Rebozo Investigation

- Emoluments and Tax Evasion

- International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT) Investigation

The AOGP was the final release of this era of tapes review; and with the Nixon’s death in 1994 only sixty-three hours of conversation had been released to the public. Despite PRMPA mandating the speedy review and release of the tapes to the public, Richard Nixon had been able to significantly delay the release of the majority of the tapes for over a decade.

-

The delay in the release of the tapes led directly to a scheduled release of tape conversations known as the chronological releases. The chronological releases was a result of the long delay and constant legal wrangling between NARA and Nixon spurred a lawsuit from historian Stanley Kutler and the advocacy group Public Citizen. Nixon’s lawyers joined the suit and in 1996 a compromise was reached. The Tapes Settlement Agreement stipulated that 201 hours of AOGP conversations would be quickly released, Cabinet Room conversations would be released next, and then the remaining tapes would be released in five chronological segments, with the fifth segment, being the largest, split into five smaller segments.

The Abuse of Governmental Power conversations were released in three parts on May 17, 1993, November 18, 1996, and February 1999 with 2,224 conversation segments totaling 258 hours from February 1971 through July 1973.

The Cabinet Room Conversations were released to the public in two parts on October 16, 1996 and February 28, 2002 and consisted of 83 tapes with 436 conversations totaling 154 hours from February 1971 through July 1973.

The chronological releases included all tapes from a date range in every location except the Cabinet Room, which were released separately. Furthermore, a process was created for the Nixon estate and other individuals who were recorded to object their release. The only outstanding issue not agreed upon was the Nixon estate’s dispute with NARA’s decision to retain a complete copy of the tapes including the “G” personal returnable segments. The Nixon estate believed those segments should be returned while NARA wanted to retain them until work was completed.

Archivists began reviewing the tapes in accordance with PRMPA regulations and the Tape Settlement Agreement. In addition to the PRMPA categories, archivists also withheld certain portions of conversations that they could not adequately review for release at the time because they were unintelligible. These portions are noted on the tape subject log as “Unintelligible.” For all of the PRMPA withdrawals (except those removed because they were unintelligible), the tape subject log noted the relevant restriction category and the duration of the withdrawal. For national security withdrawals, the tape subject log also indicated the main topic of the withdrawal.

NARA also began another tapes duplication effort in 1993. The “S Copy” had been erased during 1985-86 and the “Enhanced Copy” was beginning to exhibit sticky-shed syndrome. Sticky-shed is when the binder which holds magnetic tape together starts to degrade causing the tape to stick. Baking can counteract sticky-shed for a period of time but archivists decided it was best to create new preservations copies. Four new copies were created including a new preservation analog, the “P-Analog”, on 1.5 mm on ¼ inch open reels at 3.75 ips.

The second and third copies served as the preservation digital copy which was made on Digital Audio Tape (DAT) AMPEX #467 cassette. These are known as the “P-DATs” and from this copy a fourth copy was created, the “Edited DATS or E-DATs” which had the “G” segments erased with a 1 kHz tone. Archivists used the E-DAT to complete the first four chronological releases. All copies of the digital and analog masters were stamped with SMPTE timecode to facilitate archival work. All of the masters had the audio equalized and processed to reduce some of the noise and imperfections in the recordings. Due to the ongoing legal disputes at the time archivists were unable to listen to the “G” segments for more than a few moments to set or check the levels.

The 1st Chronological Release was made public on October 5, 1999 and consisted of 134 tapes with 3,646 conversations totaling 443 hours from February through July 1971.

The 2nd Chronological Release was made public on October 26, 2000 and consisted of 143 tapes with 4,140 conversations totaling 420 hours from August through December 1971.

The 3rd Chronological Release was made public on February 28, 2002 and consisted of 170 tapes with 4,127 conversations totaling 426 hours from January through June 1972.

The 4th Chronological Release was made public on December 10, 2003 and consisted of 154 tapes with 3,073 conversations totaling 238 hours from July through October 1972.

The next chronological releases would not come for another four years. During that time the Nixon Presidential Library, which was not part of the National Archives, became an official Presidential Library on July 11, 2007. As part of this agreement the Nixon Foundation deeded the political portions of the tapes to the federal government. Previously, all political conversations had been classified as “G” personal returnable. Those conversations could now be reviewed and released to the public. The new criteria for personal returnable was the former president’s health, his personal finances, and the private, non-public activities of the First Family (Thelma “Pat” Nixon, Tricia Nixon Cox, Edward Cox, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, and David Eisenhower). Access to the tapes was now governed by the regulations under PRMPA, the 1996 Tapes Settlement Agreement, and the 2007 deed of gift.

Under the 2007 deed of gift agreement, the Nixon Foundation also allowed NARA to retain and release room noise captured on the tapes that had been designated as “G” material under PRMPA. If President Nixon was alone in a room during a room noise recording, the room noise was withdrawn as “G” personal returnable. If President Nixon was not in the room, the room noise was withdrawn as either “G” or as “H” non-historical. Archivists reviewed these room noise segments the same as conversations, however, room noise segments were not released directly to the public, but they are available upon request.

The 5th Chronological release was the first release to include the 2007 deed of gift provisions including the release of the political “G” which had until that point been restricted. Archivists retired the E-DATs and began to use one of the P-DAT copies for review work. At the same time the Nixon Library acquired two SADiE4 Digital Audio Workstations [DAWs]. The DATs were imported into the SADiE system which staff could use to edit and output conversations to CD. Starting in 2007 conversations were simultaneously released online via the Nixon Library website. Now a more thorough record of the presidency could be obtained from the tapes, and the tapes were beginning their shift from analog to digital.

5th Chronological Release Part I was made public July 11, 2007 and consisted of 3 tapes with 165 conversations totaling 11.5 hours from November 1972.

5th Chronological Release Part II was made public on December 2, 2008 and consisted of 55 tapes with 1,398 conversations totaling 198 hours from November 1972 through December 1972.

5th Chronological Release Part III was made public on June 23, 2009 and consisted of 36 tapes with 994 conversations totaling 154 hours from January through February 1973.

5th Chronological Release Part IV was made public on December 9, 2010 and consisted of 75 tapes with 1,801 conversations totaling 265 hours from February through April 1973.

5th Chronological Release Part V was made public on August 21, 2013 and consisted of 94 tapes with 2,905 conversation totaling 340 hours from April through July 12, 1973.

The release on August 21 was the last portion of the tapes that had not been made public. After 35 years of review and multiple legal challenges archivists had finally released all of the Nixon White House Tapes to the public.

-

Even before the August 21, 2013 release, Nixon Library archivists had begun preparation for the next iteration of the tapes. In 2010 the Nixon Library submitted a proposal for funding to NARA’s Preservation Programs to create a new preservation analog copy of the tapes. Due to the 2007 deed of gift there was a significant portion of “G” conversations that needed to be reviewed and released. In 2011, NARA approved the funding with the caveat that the new preservation copy would be digital, since analog tape have gotten increasingly rare and expensive.

From June 2011 through September 2012, the Nixon Library procured the digital equipment and storage necessary for a project of this magnitude. Two SADiE6 DAWs for preservation mastering; 4 Dell DAWs with WaveLab for digital review, editing, and quality control; and 2 Synology Network Attached Storage (NAS) units were acquired. The goal of the project was to be a complete digital preservation transfer, conforming to NARA preservation standards and practices, of the “P-Analog” copy of the tapes for digital review, editing, and release.

Before archivists began digitally transferring the project, Nixon Library staff undertook a massive data digitization and modernization project in 2013 which included creating a tape dataset in an Excel comma-separated values (CSV) format that contained the following data from every single conversation: identification name, dates, times, participants, recording location, latitude and longitude, description, and other pertinent information. Archivists also took data that was locked in Microsoft Access databases––participant names, conversation subjects, and main topics––reorganized and modernized the data to comply with current archival standards. This data was placed in Excel spreadsheets and was made compatible with Extensible Markup Language (XML) to be used as metadata for digitized tapes. Staff digitized the information from the boxes tapes were housed in which would also be used for metadata and quality control. Furthermore, staff digitized every national security withdrawal into Excel spreadsheets and segregated them by recording location to aid in Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR).

The next stage of the project was the digital transfer of the “P-Analog” tapes. Following the recommendations of NARA’s Preservation Lab, the Nixon Library elected to do a flat transfer of the tapes. As discussed above, during the Chronological Review era all of the tape reels were processed and had signal boosting in order to improve audibility. A flat transfer streamlined the process and was more in keeping with current archival principles. The digital format was an uncompressed stereo Broadcast WAV––as defined by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU)––with a frequency of 96 kHz and 24 bits. The file size was going to be about 2 GB/hour and a full transfer was going to require approximately 14 TB for two preservation copies.

The digital transfer was completed by connecting a Studer to the SADiE6 system, playing the tape, and recording it in real-time into the SADiE6. Each reel was approximately one-hour long and there were anywhere from one to seven reels per tape. Once an entire tape was completed the XML data created earlier was inserted into the tape reels with BWF MetaEdit and then the entire tape was rendered out from the SADiE6 to the Nixon Library servers. From that point on archivists would work in a digital environment and would open the reels in WaveLab to conduct quality control. During the quality control process archivists checked the audio levels, SMPTE timecode levels, metadata, and overall soundness of the digital file. If the file passed quality control MD5 checksums were embedded and two clones of the files were created and placed on different servers. If the file did not pass quality control, it was sent back to be re-digitized to fix the error. The complete digitization of the tapes is scheduled to be completed by Fall 2018.

With the preservation process underway archivists began working to develop the next steps for processing national security information. By 2012 all national security withdrawals had been officially requested through MDR procedures. Archivists used the MDR requests to create a queue for which tapes were to be processed and reviewed first. Archivists needed to simultaneously develop processes for MDR in addition to the tapes review process already in place. Therefore, the Nixon library developed a two-pronged strategy to accommodate both MDR and tape review. In order to process tapes, archivists began another digitization project. This project involved taking analog determination sheets––which document the SMPTE timecode beginning and end of each conversation, room noise, and withdrawals––and digitizing them. These would be used in conjunction with WaveLab to create montages. Montages are like onion skins that archivists can use to modify and markup the tapes without changing the files. To complete a montage an archivist has to digitally splice together each reel to recreate a complete tape––which were broken up into separate one-hour reels during preservation––and then add in markers for conversations, withdrawals, and room noise. After a montage is completed, the tape is then ready to be processed for MDR review.

Next archivists developed a new method for MDR review. The necessary data was digitized, but archivists now needed a way to automatically populate the data in analog sheets. These sheets would be given to the various equity holders to facilitate their review of restricted segments. Furthermore, archivists needed a way for the MDR reviewers to listen to the various segments. To solve the first problem archivists created new MDR review documents, based on the textual model, but with important changes that reflected the audio nature of the collection. Archivists then used mail merge in Microsoft Word to pull from various Excel spreadsheets to automatically populate MDR documents. It was important for archivists to move away from the CD model of the Chronological Review era so that they could harness all the advantages of the digital format. CDs are also expensive, inefficient, and need to be disposed of properly. The Nixon Library decided to invest in five Sony Walkman NW-E390 MP3 players. With these archivists could load playlists for reviewers and they could harness the metadata they had to embed in MP3’s identifying information which would aid MDR reviewers.

With these issues settled archivists began the process of getting every national security withdrawal reviewed. They also had to re-review all the “G” withdrawals from the 1st through the 4th Chronological review. Using the methods developed by their predecessors, archivists began to review the tapes for content. Much of tape review remains the same. A tape is reviewed by two archivists to ensure compliance with PRMPA, the Tapes Settlement Agreement, and the 2007 deed of gift. There are some areas where current tape processing is different however. Previous eras, inserted a 10 sec 1 kHz tone into every withdrawal. Mainly, this was done because of the limited space available on CDs and audiocassettes. With the tapes completely digital archivists edit out the restricted segment and insert in a 1 kHz tone of the same length as the withdrawal. When a tape is finished, each conversation is rendered out separately as a high-quality mono uncompressed Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) Broadcast WAV EBU at 44.1 kHz and 24 bits. Those Broadcast WAVs are then embedded with metadata at the conversation level. The WAVs are then converted into MP3s at 320 kbps, metadata added as needed, and then are posted to the website as the public access copy of the tapes.

Some of the overriding goals of this review of the tapes was to bring all tapes into conformity with the 2007 deed of gift. There are large segments of political conversations that are now going to be available to the public for the first time. Simultaneously, archivists are updating and standardizing the tapes finding aid. The finding aid––which has been created at different times, with different technology, and different standards––needed to be brought up to modern archival standards. This standardization includes language and appearance. One major change is how “unintelligible” withdrawals will now be treated like every other withdrawal on the tape subject logs with identification information and duration. Previously, the logs marked these withdrawals only with [unintelligible] but no other identifiable information or duration. This change will improve transparency between archivists and the public.

Building upon the work of previous archivists to improve both the clarity and consistency of tapes and finding aids was paramount. Previous eras had to contend with reviewing tapes and at the same time potential legal threats. With those threats now removed, archivists had the time to standardize the language and update decision-making processes to more closely align the entire collection with current archival standards. To accomplish this an internal manual was created with detailed work-flows and best practices. Training to review tapes is intensive and archivists seek to form a collaborative atmosphere in order to best interpret the various laws and regulations ensuring compliance with the law and maximum public transparency. With all archivists on the same page there will be a uniformity of purpose and practice that will create a better product for the public.

In the Spring of 2018 the Nixon Library released the first batch of new tapes with the intent to release new tapes in full after review and MDR work is completed. As of September 2018 all 4,042 reels of the Nixon White House Tapes have been digitized.

Bibliography

-

“Audio Maximum Capture [AUD-P1].” n.d. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed August 7, 2018. http://www.archives.gov/preservation/products/products/aud-p1.html.

Conway-Lanz, Sahr. 2011. “The Nixon Tapes.” Essay. In A Companion to Richard M. Nixon, edited by Melvin Small, 546–62. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Haldeman, H R. 1988. “The Nixon White House Tapes: The Decision to Record Presidential Conversations.” Prologue, 1988. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1988/summer/haldeman.html.

Hoff, Joan. "Researchers' Nightmare: Studying the Nixon Presidency." Presidential Studies Quarterly 26, no. 1 (1996): 259-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27551564.

Krusten, Maarja. n.d. “White House Tapes Scope and Content Note.” White House Tapes Scope and Content Note.

Kutler, Stanley I. 1992. The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon. New York: Norton.

“Magnetic Tape Binder Breakdown.” n.d. Preservation Self-Assessment Program. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign . Accessed August 7, 2018. https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide/softbindersyn.

Powers, John. 1996. “The History of Presidential Audio Recordings and the Archival Issues Surrounding Their Use.” National Archives Career Internal Develop System [CIDs] Paper, July.

“Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act (PRMPA) of 1974.” n.d. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed August 7, 2018. . http://www.archives.gov/presidential-libraries/laws/1974-act.html.

“Press Release nr96-61.” 1996. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. April 12, 1996. https://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/1996/nr96-61.html.

Rushay, Samuel W. 2007. “Listening to Nixon: An Archivist’s Reflections on His Work with the White House Tapes.” Prologue, 2007. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2007/fall/tapes.html.

SAA Newsletter 1982-07. 1982. “SAA Newsletter,” July 1982. http://files.archivists.org/periodicals/Archival-Outlook/Back-Issues-1973-2003/saa_newsletter_1982_07.pdf.

SAA Newsletter 1987-01. 1987. “SAA Newsletter,” January 1987. http://files.archivists.org/periodicals/Archival-Outlook/Back-Issues-1973-2003/saa_newsletter_1987_01.pdf.

SAA Newsletter 1987-05. 1987. “SAA Newsletter,” May 1987. http://files.archivists.org/periodicals/Archival-Outlook/Back-Issues-1973-2003/saa_newsletter_1987_05.pdf.

“Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities.” 2018. U.S. Senate: Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities. U.S. Senate. July 31, 2018. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/investigations/Watergate.htm.

Worsham, James. 2007. “Nixon’s Library Now a Part of NARA: California Facility Will Hold All Documents and Tapes From a Half-Century Career in Politics.” Prologue, 2007. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2007/fall/nixon-lib.html.

-

As detailed in the processing history of the White House Tapes, the National Archives has spent considerable time preserving, reviewing, and making access to the White House Tapes. Gathered below is a collection of additional finding aids and tools developed over the years. Many of these have been replaced or supplemented by additional archival work.

Complete Chronological Processing

Tapes Chart

Helpful collection-level chart dividing up tapes by recording location, month and year, and archival processing segment.

Abbreviations

Participants in each conversation received abbreviations of their initials as identifiers with President Richard Nixon abbreviated as “P.” Cataloging about each conversation included those abbreviations and this document defined those abbreviations. Staff have worked to move away from abbreviations and toward full names.

Database reports

Portable Document Format (PDF) versions of reports from a database tracking all conversations on the tapes.

Obsolete Lists

The following lists incorporate information for the First through Fourth Chronological Releases (Feburary 1971 - October 1972), as well as Cabinet Room conversations (February 1971 - July 1973). They do not include information from the Fifth Chronological Release (November 1972 - July 1973). The lists have been supplanted by the search functionality in the Portable Document Format (PDF) Index.

A list of each acronym used in the Tape Subject Logs. The list details the word from which the acronym was derived and refers to the tape number on which the acronym occurs. Entries in red indicate the mention was on a tape available on CD rather than cassette.

A list of geographic locations that appear in the Tape Subject Logs along with the tape number(s) in which the location is a subject. Entries in red indicate the mention was on a tape available on CD rather than cassette.

A list of individuals whose names can be found in the Tape Subject Logs and the tape number(s) in which the person is a subject or participant. Entries in red indicate the mention was on a tape available on CD rather than cassette.

Scope and Content Notes

For each release of tapes, staff wrote an archival finding aid including information about the collection, its processing, and a broad content overview. The most specific listing of information on a tape remains the Tape Subject Log.

First Chronological Release Scope and Content Note Second Chronological Release Scope and Content Note Third Chronological Release Scope and Content Note Fourth Chronological Release Scope and Content Note Fifth Chronological Release, Part I Scope and Content Note Fifth Chronological Release, Part II Scope and Content Note Fifth Chronological Release, Part III Scope and Content Note Fifth Chronological Release, Part IV Scope and Content Note Fifth Chronological Release, Part V Scope and Content Note Excerpted Processing

The National Archives also created finding aids and tools to help locate and navigate releases of conversations or parts of conversations. Specific releases included in Excerpted Releases finding aids include the Watergate Trial Tapes (tapes and transcripts), Watergate Special Prosecution Force (tapes and transcripts), and Abuse of Governmental Powers (tapes and logs). NOTE: Cabinet Room declassified segments designated as excerpts.

Abuse of Governmental Powers (AOGP)

Abuse of Governmental Powers Logs